FormScore Evidence Review

Dr Iain Jordan | MB MSc MRCPI MRCPsych | Consultant in Psychological Medicine at Oxford University Hospitals and Mental Health Academy Lead at ZINC

Introduction

Form is a novel digital product which combines instant messaging functionality with a regular user-rated wellbeing score (FormScore, Figure 1). Users are encouraged to follow the Form of others in their circles via a “Radar” facilitating a peer support network with regular messaging exchanges.

This review aims to explore the relationship between engagement in online communications systems - especially instant messaging - and psychosocial outcomes. It also aims to explore the rationale for combining this communication modality with a self-rated wellbeing score and peer support.

Engagement in online communication systems and psychosocial outcomes

The top 3 instant messaging apps together (Whatsapp, Facebook Messenger and WeChat) have 4 billion daily active users (Bucher 2020). 75% of Whatsapp users use it every day (Iqbal 2020). Instant messaging overtook SMS by number of messages sent in 2012 (Informa 2013) and has continued to grow since. What effect does this, now virtually ubiquitous, form of communication have on psychosocial outcomes?

There is evidence that the use of instant messaging enhances relationships and users’ perceptions of social support (Chan 2018) and is associated with better relationship satisfaction and reduced loneliness (Park et al 2016). Perceived social support appears to be a better predictor of mental health than actual, or received support (Wethington & Kessler 1986). Such online bonding, enhanced through the use of instant messaging platforms, mediates positive psychosocial outcomes (Kaye & Quinn 2020).

There is continued debate around the potential positive and negative consequences of online communication with respect to mental health (Tsai et al 2019). There are also likely to be group differences - for instance older users of social media have fewer online friends but those friends are more likely to be real-world friends - suggesting that this age group uses social media to enhance bonds rather than enlarge networks (Chang 2015).

As the near-universal recent experience of lockdown during the coronavirus pandemic has emphasised, mobile communications provide an invaluable mechanism for connection and social support when people are geographically isolated.

Figure 1. Prompt for Form self-rating

Online Self-disclosure and Self-rating

There is a plausible relationship between reflecting on emotional states - and communicating them to others - and improved mental health. Emotional awareness is associated with better mental health (Sendzik et al 2017), and emotional disclosure is associated with significant psychological benefits (Frattaroli 2006). Research suggests that mood monitoring itself is not sufficient to affect wellbeing but when it is combined with access to health information it provides a mechanism for eliciting self-help (Scherr et al 2019). Digital platforms designed to encourage reflecting and sharing emotion among users find improved communication and social support (Gay et al 2011, Church et al 2010).

Despite a bias toward expressing positive rather than negative aspects of ourselves online - the “positivity bias” - authenticity in online communications is associated with improved wellbeing (Reinecke & Trepte 2014). Self-disclosure is one of the defining characteristics of close relationships. Such vulnerability, conceptualized as “uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure” may be fundamental to feelings of belonging and closeness (Brown 2012). Instant messaging stimulates self-disclosure and the relationship between use of instant messaging and improved quality of relationships appears to be mediated by such disclosure (Valkenburg & Peter 2009). Online interactions lend themselves to self-disclosure (Suler 2004) and large studies of self-disclosure of distress on social media sites Reddit (Balani & De Choudhury 2015) and Instagram (Andalibi et al 2017) have shown that high self-disclosure is associated with a sense of community and social support via high levels of engagement and support by other users.

Discussion

There is debate about the relationship between online forms of communication and psychosocial outcomes. The continued rapid growth in the use of instant messaging apps indicates that this is, and will continue to be, an important way in which relationships are formed and maintained. It scarcely needs to be said that there are positive and negative experiences with respect to online communications - but if methods of self-disclosure and support are integrated into such a ubiquitous form of communication, the research described herein suggests that the effect will be to enhance relationships, reduce stigma, and facilitate social and professional support.

The biggest challenge for mental health apps is that people are typically motivated to use them when very distressed and there is a precipitous drop off in usage after initial download. The great potential of Form is that a potential solution to this problem is baked into the design. 75% of Whatsapp users use it every day (Iqbal 2020) - this regular use, if it can be replicated in the Form app, provides an automatic prompt with a linked behaviour involving reflection, connection, and support (FormScore).

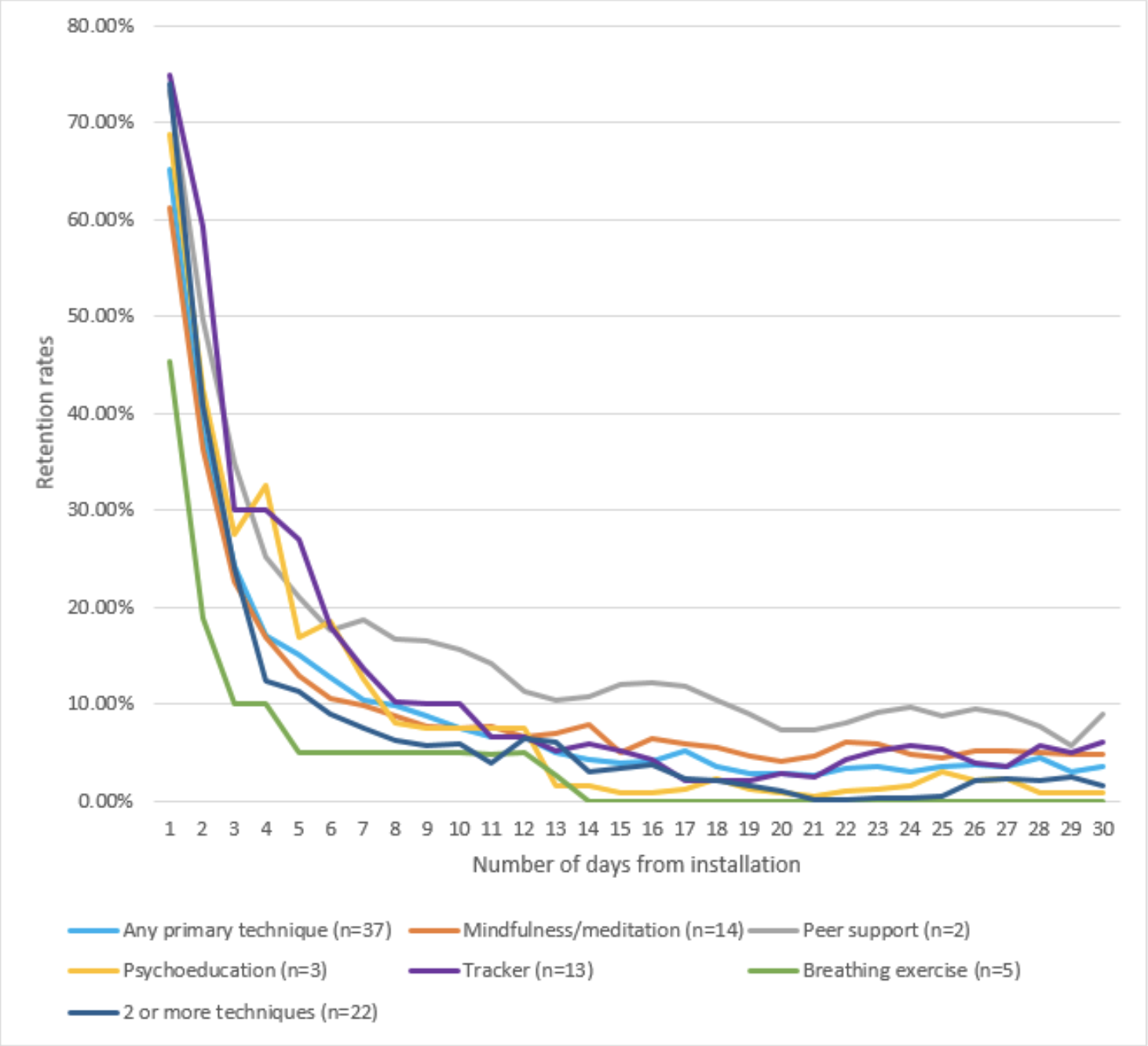

Research indicates that when mood monitoring is combined with access to health information it provides a mechanism for eliciting self-help and there are known benefits to reflecting on emotional states, and emotional awareness. When self-rating is paired with psychoeducation, peer-support, or evidence-based digital psychotherapeutic interventions, the same is likely to be the case - indeed mental health apps with a peer-support component have higher retention rates than other types of intervention (Baumel 2019, Figure 2) - especially if those peers have had specific training on how to helpfully respond to contacts in distress.

Figure 2. Mental health apps with a peer-support component have higher retention rates than other types of intervention (Baumel 2019)

Risks and Proposed Directions for User Feedback and Research

Being permanently connected to the internet and therefore to one’s friends, colleagues, and acquaintances is one of the major advantages of mobile devices. There is a tension here too though and some users find this always-on connectivity burdensome (Hall et al 2012). There is a possibility that the added features of self-disclosure and support may affect both sides of this equation - i.e. enhance support but also enhance a feeling of responsibility and burden.

Some aspects of instant messaging known to have negative consequences for mental health (e.g. Tsai et al 2019) may interact with the novel features of Form. For instance, feelings of loneliness or rejection engendered by a lack of response could be exacerbated by the self-disclosure inherent in the platform. These potential consequences should be investigated.

Reflecting on negative mood and negative events temporarily depresses mood. The effects of self-rating using Form when mood is lower should be investigated.

Construal level theory holds that when objects or events are examined at a psychological distance they are evaluated in a more abstract way (higher construal level) than events that are psychologically close. This may be why we are able to observe and evaluate others’ difficulties more dispassionately than our own (Horvath 2018). It is possible that communicating a one-dimensional, numerical rating (as in the Form rating) of one’s subjective state, could provide a higher construal level, and therefore be less distressing than elaborating details of one’s difficulties. This would be an interesting avenue for research.

The Form score is not a validated rating scale, and it is not currently known whether and to which valid and well-defined psychological constructs in various populations it corresponds. Establishing this would enable a bridge between user experience and outcomes, and existing psychological research.

References

Andalibi, N., Ozturk, P., & Forte, A. (2017, February). Sensitive Self-disclosures, Responses, and Social Support on Instagram: the case of# depression. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM conference on computer supported cooperative work and social computing (pp. 1485-1500).

Balani, S., & De Choudhury, M. (2015, April). Detecting and characterizing mental health related self-disclosure in social media. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1373-1378)

Baumel, A., Muench, F., Edan, S., & Kane, J. M. (2019). Objective user engagement with mental health apps: systematic search and panel-based usage analysis. Journal of medical Internet research, 21(9), e14567

Brown, B. (2012). Daring greatly: how the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent and lead. London: Penguin.

Bucher, B. (2020, February 13). Messaging App Usage Statistics Around the World. Retrieved June 10, 2020, from https://www.messengerpeople.com/global-messenger-usage-statistics/

Chang, P. F., Choi, Y. H., Bazarova, N. N., & Löckenhoff, C. E. (2015). Age differences in online social networking: Extending socioemotional selectivity theory to social network sites. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 59(2), 221-239.

Church, K., Hoggan, E., & Oliver, N. (2010, October). A study of mobile mood awareness and communication through MobiMood. In Proceedings of the 6th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Extending Boundaries (pp. 128-137).

Frattaroli, J. (2006). Experimental disclosure and its moderators: a meta-analysis. Psychological bulletin, 132(6), 823.

Gay, G., Pollak, J. P., Adams, P., & Leonard, J. P. (2011). Pilot study of Aurora, a social, mobile-phone-based emotion sharing and recording system.

Horvath, P. (2018). The relationship of psychological construals with well-being. New ideas in psychology, 51, 15-20

Informa (2013, April 30). Retrieved June 10, 2020, from https://www.informa.com/media/press-releases-news/latest-news/ott-messaging-traffic-will-be-twice-volume-of-p2p-sms-traffic-this-year/

Iqbal, M. (2020, April 24). WhatsApp Revenue and Usage Statistics (2020). Retrieved June 10, 2020, from https://www.businessofapps.com/data/whatsapp-statistics/

Kaye, L. K., & Quinn, S. (2020). Psychosocial Outcomes Associated with Engagement with Online Chat Systems. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 36(2), 190-198.

Park, N., Lee, S., & Chung, J. E. (2016). Uses of cellphone texting: An integration of motivations, usage patterns, and psychological outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 712-719.

Reinecke, L., & Trepte, S. (2014). Authenticity and well-being on social network sites: A two-wave longitudinal study on the effects of online authenticity and the positivity bias in SNS communication. Computers in Human Behavior, 30, 95-102.

Scherr, S., & Goering, M. (2019). Is a self-monitoring app for depression a good place for additional mental health information? Ecological momentary assessment of mental help information seeking among smartphone users. Health communication, 1-9.

Sendzik, L., Schäfer, J. Ö., Samson, A. C., Naumann, E., & Tuschen-Caffier, B. (2017). Emotional awareness in depressive and anxiety symptoms in youth: A meta-analytic review. Journal of youth and adolescence, 46(4), 687-700.

Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychology & behavior, 7(3), 321-326.

Tsai, H. Y. S., Hsu, P. J., Chang, C. L., Huang, C. C., Ho, H. F., & LaRose, R. (2019). High tension lines: Negative social exchange and psychological well-being in the context of instant messaging. Computers in Human Behavior, 93, 326-332.

Wethington, E., & Kessler, R. C. (1986). Perceived support, received support, and adjustment to stressful life events. Journal of Health and Social behavior, 78-89.